The Pilgrim’s Path

So you’ve already heard the Good News? Blessed are you in the eyes of Ludd, already and truly. Do you count yourself among the Faithful, or has a sense of spiritual longing brought you to this shrine? Perhaps you’ve visited Beholder Station before? Have you contemplated the clouds of Kumari Aru, that sacred cradle of xenolife, which may be observed from the inner shrine? Many pilgrims speak of feeling a spark of the divine when contemplating the multitudes of Creation…

This is a sort-of a part 3 in the faction series but with more of a David-style focus, that is, on the writing, world-building, and implementation of a new set of missions, though I admit that the word “quest” in this case might have the right feel.

(I would carry on Alex’s blog title series but I simply can’t bring myself to write the word “uniquifying” more than this once. It’s just, *shudder*, one of those words.)

ALL HE EVER GIVES US IS PAIN

All of which is to say: I’m going to be writing about some new content for Starsector which involve the various Luddic factions: the Church, the Knights, and a touch of the Path. In particular, this is a new mission which involves visiting a series of Luddic shrines, having some encounters along the way, and taking a stance on Luddism in general.

There will be spoilers herein, but worry not, Citizen! There’s no SUPER ALABASTER REDACTED to bring the fury of COMSEC down upon us. That said, if you want everything to be a surprise, then you won’t want to read this post. But if you’d like a peek into the design and creation of some of the introductory content for the Luddic factions, then read on. We’ll start with some general background, design, and process discussion then actually show off new content as the last section. You’ll get another warning before that starts up.

Let us begin in the beginning, with first principles that flow from the essential question: What the heck is Luddism?

MUSINGS ON THE PHILOSOPHICAL BASIS OF LUDDISM

Working assumptions:

- They’re called the “Cult of Ludd”

- They don’t like technology

- They’re religious?

And that’s about what I started with based on Ivaylo’s original drafting of the Starsector setting. I suppose I could have pushed to rewrite “The Cult of Ludd” entirely into something else, but from a gameplay standpoint we do need some baddies to shoot, and past that I do think there’s a really interesting and relevant idea in the faction(s) which can serve to turn a critical mirror toward this scifi setting.

So what are these people even about? In writing the Pilgrim’s Path, I had to figure out how to provide more answers to these questions than I have previously. Speaking of, I do have a very old document from perhaps a decade ago where I wrote out my thoughts on the background of all the factions.

I’ll quote a section from the “Cult of Ludd”:

In extremely broad terms: The Luddic Faith is a bit like early Christianity. A more conservative & hierarchical church structure is forming (The Church of Galactic Redemption), though it’s doctrine still has (many) conflicts to be resolved. The church has a militaristic arm (The Knights of Ludd) which, from a certain point of view, is at odds with the prophet Ludd’s generally anti-militaristic message but is terrifically practical. Militant extremist elements exist outside of control of the Church hierarchy and their values do not mesh well with contemporary Sector society (such as it is), to put it lightly.

And from the next section “Who is Ludd?”:

A revolutionary/spiritual figure with an impressive and divisive legacy. Active in the cycles leading up to the fall of the Gate system, gave a message that was somewhat apocalyptic / of need for humanity to reform, to turn away from the excesses of the Domain. All sorts of things have been attributed to Ludd and if half of them are true then Ludd would have been at once a nihilistic megalomaniacal cult-leader and a saint who brought a wave of spiritual reform that swept away the detritus of millennia of cruelty and corruption.

So that’s all been roughly doctrinally consistent since the start. Good jobs all around.

*nervously eyes a cadre of power-armoured Knight-Inquisitors*

I should take this moment to make an important point: Luddics are not Luddites. Obviously they’re inspired by Luddites, the historic workers’ movement in industrializing England (that smashed machinery because their livelihood was being destroyed rather than any nonsense about fearing technology), and by the broader term “luddites” as used pejoratively against those who are fearful, ignorant, or critical of technology. But I try to make it very clear through the use of a unique (albeit related) terminology that they’re their own thing which exists in their own science fictional context.

My thinking is that, like the most common usage of the term “luddite”, this group got called “luddites” as a term of disparagement — then they adopted the term and wore it with pride in an act of reappropriation. This happens all the time in history, so why not here? It’s on-the-nose, but sometimes the names people call other groups of people are on-the-nose.

WORLDLY MATTERS

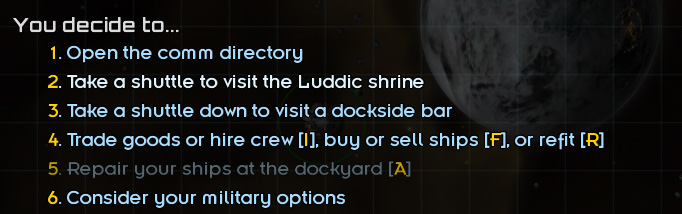

In one world, this mission would see the player following an exclamation mark. Once arrived, they’d keyboard smash through some dialog and check an item off the list ’til all the checkmarks are collected and the XP rewarded.

… And indeed, we live in that world! You can do that if you like! (Remember: just smash that “1” key through all dialog options and you’ll get to the end eventually.)

But if this set of missions was simply about visiting a place and checking it off the list that’d be super boring. Even worse, I would be disappointed with myself for creating something as boring as that when I had an opportunity to be extremely weird and a little intense instead!

For inspiration I look, as ever, to the bizarre masterpiece of game worldbuilding that is Morrowind.

Now there’s a game that makes learning about religion interesting! (Allegedly assisted by certain chemical influences that would turn a contraband inspection patrol officer red, if the stories are true. I salute the devotion of those developers to their craft!) Morrowind speaks for itself, maybe, so I won’t try to describe it. I would want to take some imperatives from that game, however, to do with taking its own expression of a world seriously and being devoted to carrying it through as intensely and weirdly as need be.

Anyway, my drug of choice is mostly coffee.

Back to Luddism: no religion is a monolith of belief. Keeping doctrinal purity, particularly over interstellar distance and across borders, is like building a tower out of dry sand. It’s a constant effort to pull outliers back into line, and meanwhile all sorts of people keep finding all sorts of ways of relating to and interpreting the tenets of the Luddic faith.

Shrines give us a way to show this: each shrine is on a different world with its own problems, factions, and people, and themes. The shrine of Jangala, for instance, involves some conflict between the secular Hegemony authorities and the Luddic faithful’s relationship (such as it is) with the native xenolife. These all build on existing elements within the game world while providing them with another set of viewpoints/commentary – and, naturally, opportunities for the player to get involved and cause a bit of trouble.

(Or make some friends? I don’t know. Sebestyen was a big hit with certain players; I didn’t quite expect that.)

Let’s do the deep-dive on one shrine visit which is more or less completed to show what I mean.

[This is definitely spoiler territory! This is your warning to avert your eyes lest ye see unwanted revelations!]

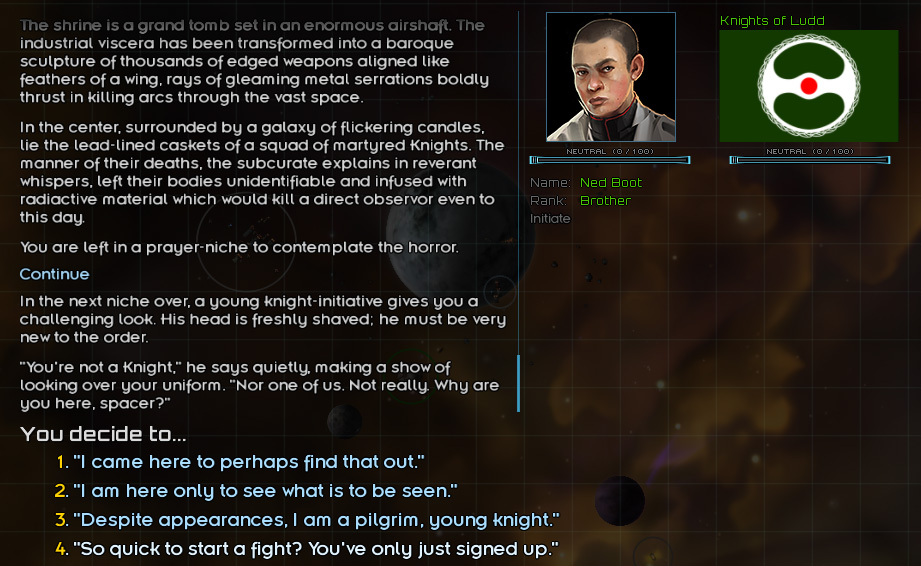

THE SHRINE OF HESPERUS

The Pilgrim’s Path mission is initiated after the player visits one of the public Luddic shrines then expresses to the local Curate Sacraria, the shrine’s head priest, an interest in visiting the others. This interest can be secular, religious, or even cynical (which may become important later). Also, most shrines are not accessible until the player makes it an explicit goal to visit them.

(Alex did kindly implement a nice feature where you can run into pilgrimage fleets. If you talk to them, they will tell you what they’re up to. And yes, if you blow these fleets up, it’ll make the Knights really unhappy with you.)

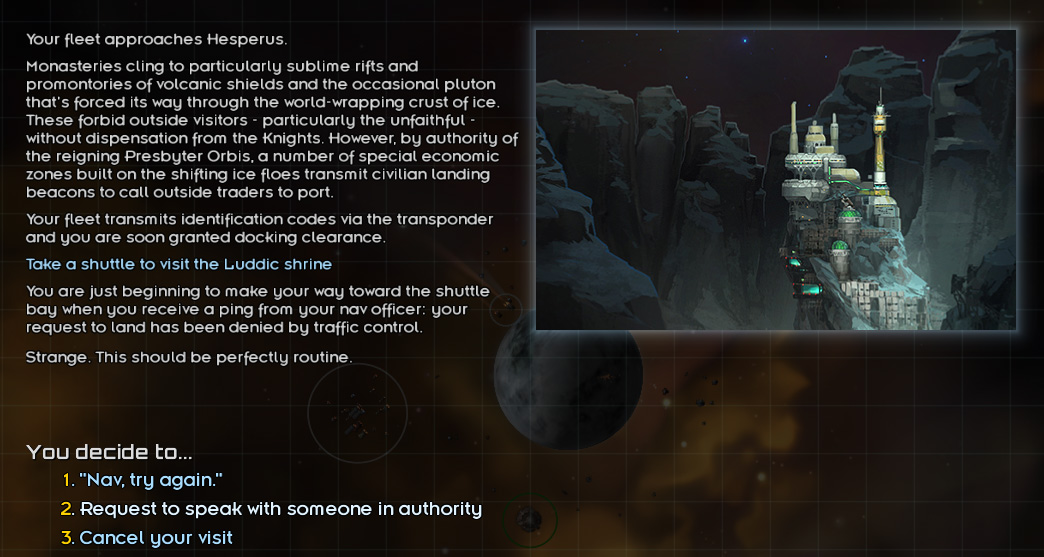

Hesperus, for instance, is a world closely controlled by those Knights of Ludd. They are somewhat suspicious of outsiders, especially outsiders like the player.

Let’s visit the shrine.

Here we go.

Only to discover that one does not simply shuttle into Hesperus.

The Hesperus shrine was a bit of a last minute thought on my part. Originally, a different planet was going to get a shrine, but then I realized that we needed an opportunity to introduce the Knights of Ludd to the player who is getting interesting in Luddic faction business, and what a great opportunity this would be!

Up until now, the Knights of Ludd have not received much in the way of development. They’ve just been described at a high level as a monastic order of future knights-militant, vaguely involved in some historical battles, and not much else in terms of the campaign.

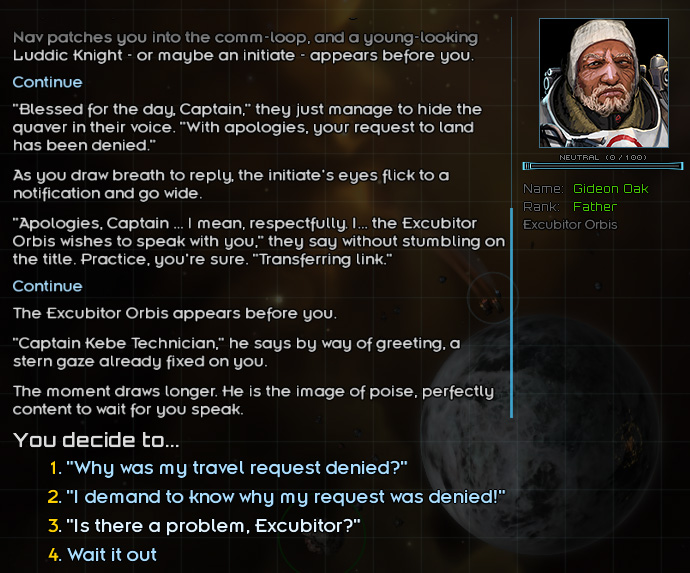

Let’s meet the Excubitor!

(Portrait art is in-progress, by the way.)

And, naturally, for this encounter the Knights are an antagonist. Why? Because they’re sticklers for rules, for self discipline, for restraint, for acting piously. Basically nothing like the average player.

Let’s see if we can’t work something out…

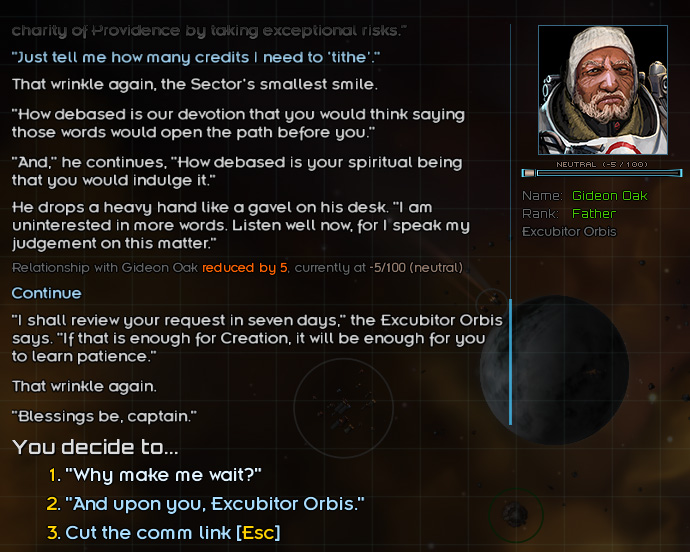

Of course not, he’s a Knight! They don’t do things the easy way. The whole notion annoys them. Indeed, most things in particular annoy Excubitor Orbis Gideon Oak.

He’s going to make me wait – so at least there’s still a door open. (His reactions, by the way, are based on your reputation. If you’re actually liked by the Knights already, somehow, this goes more easily.)

Still, maybe you don’t want to wait a symbolic seven days while the Excubitor says condescending things at you. Clever players may find a way around this little bureaucratic delay; maybe do something sneaky, maybe find someone who is much more broad-minded about the use of below-the-board currency transfers to smooth business along. I’ll leave it to you to find out.

You can also play it straight and do your best to be good and follow the rules. The Knights probably like that stuff, and if you’re role-playing a captain who is trying to take this whole Luddic faith thing seriously, then that’s an option.

Let’s say you get through it somehow and jump to the next section.

This is placeholder shrine art, by the way. Alex was like, “You’re going to do an illustration for this, right?” And I’m like, “Oh. Uh. I… yes? Yes, I definitely expected to have to illustrate this when I decided to churn out some purple description of a huge pile of intricate 40k leftovers.”

I should mention also, Alex did give me a fun new display option for some of the planetary approach dialogs: a “ShowLargePlanet” command that really emphasizes the planet during dialog. He also provided a “HideVisual” command that hides all images and shows just the dim campaign background alongside the dialog. Using these and other tricks at appropriate times is subtle, but I’ve been surprised to find that it significantly affects the mood of dialog as you’re playing through it.

(Portrait art in-progress, etc.)

Then we meet this kid.

Let me talk for a moment about process. Going into writing this shrine, this is about the full extent of my planning notes:

It’s still mostly accurate, but obviously introducing another new character in the shrine wasn’t part of the plan.

Most of the other shrines were largely written out beforehand, actually. See, I had a week in March when I was working off my laptop so I just wrote lots of Starsector content and otherwise tried to avoid having to do art on a small screen. But, you know how it goes, no plan survives contact with the enemy. The enemy, in this case, being my desire to do weird stuff when I feel like it’d be fun.

To implement these encounters I start at the beginning and start writing. When I reach a point where the player can give their own responses, I try to come up with a handful of natural-feeling replies, then I see where they lead. Sometimes they lead to strange places that take a lot of effort to implement; sometimes this gets out of hand and I trim that branch out. Sometimes I don’t (often because Alex is like “No, we have to do it!”).

To my own mind, it’s a bit like running a D&D game and imagining players going through then trying to respond to their choices, then seeing where that leads. Except it’s all in my head, and I’m trying to imagine you playing through it. Anyway, I’ve written about this before; it’s fun. Let me focus on those dialog responses though.

For this mission in particular, I set things up to track the way the player expresses their attitude toward the Luddic faith in general through the replies they choose in dialog. I’m trying to get a feel for what role the player is trying to position themselves as, and it’s more than “I want them Luddics to like me” vs “I want the Luddics to hate me”. I want to know if the player is acting like they want to be a part of the Church, whether they truly believe, or whether their attitude is more cynical. Or maybe they want to respect the Luddics but don’t believe in the religion. Or they believe in the religion but think Brother Cotton and the Luddic Path really has the right way of it…

Basically, my goal is that by the end of the Pilgrim’s Path mission I (or if you like, the game) have an idea of how the player’s character relates to the Luddic faith. From there, we can do some interesting stuff with factions which, sadly?, to not fall within the scope of this blog post.

Now where were we?

The kid. Right.

The thought that erupted into my mind at this point in writing the dialog was that I needed to have another reflection of who the Knights were. You’ve already met Gideon Oak, and like his namesake, his position on all matters before him is hardened and unyielding. Where did someone like that come from? Could they make different choices, come to different conclusions?

What if we let the player have a talk with an impressionable young Knight-Initiate who is, while aggressive about their adopted cause, a bit confused about what they actually want? (And what trouble could this lead to?)

It’s not a long conversation, but once I realized that these questions were begging to be expressed, I had to go for it. And, sigh, write another intercharacter conversation with a whole tree of options and a custom character portrait and so on.

I’m not going to show you where this conversation goes because you’ll have to play the game and make your own choices to find out.

For each and every shrine, like I’ve shown here, I’ve tried to find an angle on Luddism to explore how people in-universe relate to their faith, and then try to give the player a way to react to that.

(You do, also, check off a list of shrines and get experience for visiting them. This is, after all, a game. It’s funny, though; moving the exact line where this feedback is given, where it says “Gained X experience”, can completely undermine the mood set by the writing by having the game’s gamification burst in at the wrong moment. Which is why, incidentally, cheevos are a terrible invention.)

Honestly, this has been a difficult set of dialogs to write, but also very rewarding once they get to a place I’m happy with. I think I’ve done a reasonable job of taking the setting seriously, being true to the weirdness that results, and giving players something interesting to do with their time while exploring this space.

And I’ve got a lot more to write before it’s over.

Comment thread here.

Tags: look out for cliffracers, lore, Luddic Church, luddics, skulls, writing